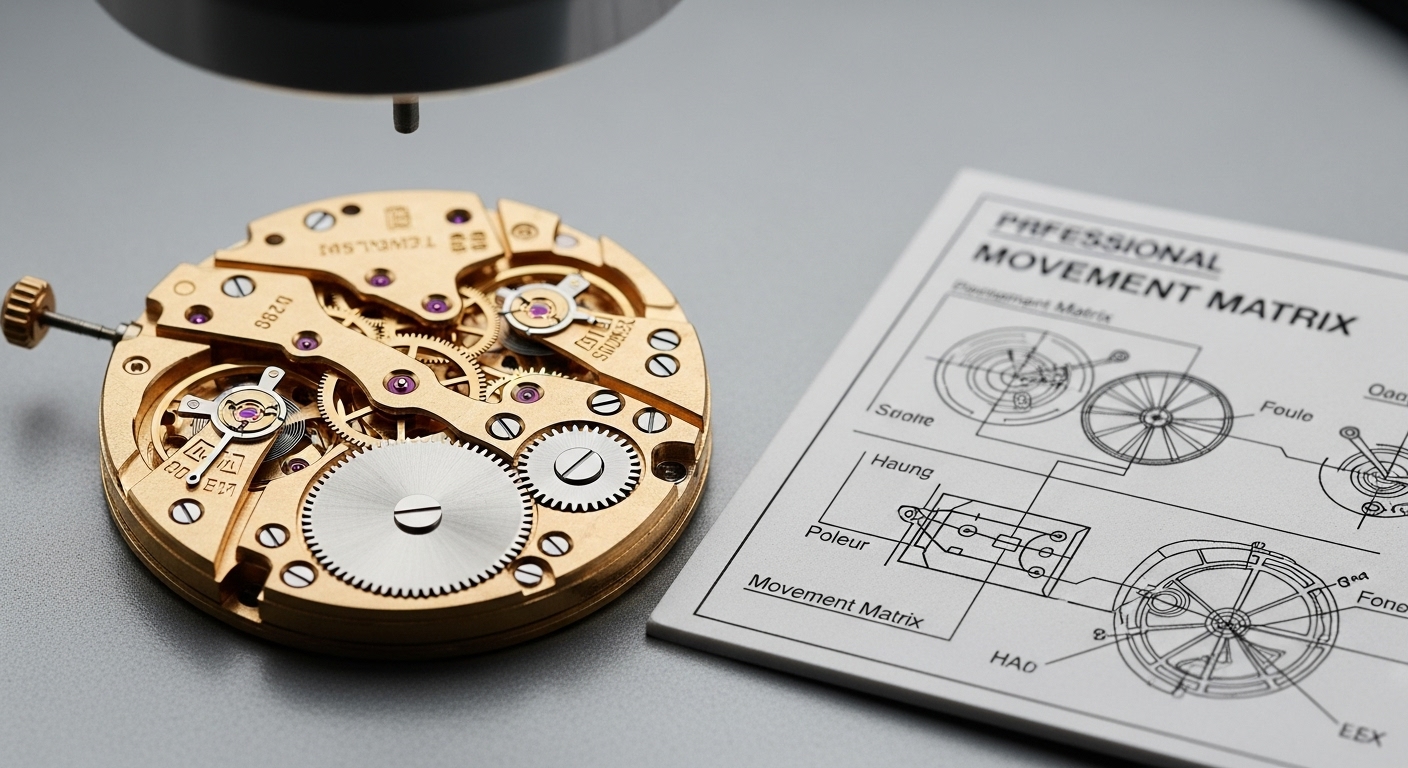

The world of watches can feel intimidating, a complex universe of tiny gears, springs, and cryptic terminology. Yet, at the core of every single timepiece, from a simple digital display to a grand complication, lies its engine; what horologists call the movement. This is the heart that gives a watch life, the intricate mechanism that measures the passage of time. Understanding this engine is the first and most crucial step to truly appreciating the art and engineering of watchmaking. But where does one begin? We propose a simple framework, the ‘Movement Matrix’, a system for categorizing and comprehending any watch’s movement. This guide will demystify the technology ticking away on your wrist. We will explore the fundamental divide between quartz and mechanical power, differentiate between manual and automatic winding, examine the roles of both third-party and prestigious in-house movements, and finally, touch upon the fascinating world of complications and artistic finishing. By the end, you will have a clear mental map to navigate the soul of any watch.

The foundational split quartz versus mechanical

Every watch movement falls into one of two primary families; quartz or mechanical. This is the most fundamental distinction in the world of horology. A quartz movement is, in essence, a tiny computer powered by a battery. The battery sends an electrical current through a small quartz crystal, causing it to vibrate at a precise frequency, typically 32,768 times per second. A circuit counts these vibrations and uses them to generate regular electrical pulses, one per second, which drive a small motor to move the watch hands. This technology, popularized in the 1970s and 80s, is incredibly accurate, durable, and inexpensive to produce. The tell-tale sign of a quartz watch is the distinct ‘tick-tick’ motion of the seconds hand as it jumps once every second. Quartz watches represent the peak of practical timekeeping, offering grab-and-go convenience and reliability that is hard to dispute. Many of the world’s most popular watches rely on this trusted technology for its affordability and precision.

On the other side of the spectrum lies the mechanical movement, a traditional engine powered not by a battery but by the controlled release of energy from a coiled spring called the mainspring. This is a miniature world of gears, levers, and jewels working in harmony, a purely analog machine. A mechanical movement is a living thing on your wrist, its balance wheel oscillating back and forth, creating the smooth, sweeping motion of the seconds hand that enthusiasts adore. It lacks the pinpoint accuracy of quartz and requires more delicate care, but it possesses what many call ‘soul’. The craft, tradition, and hundreds of years of innovation packed into such a small space create a deep connection between the watch and its owner. As one watchmaker famously put it;

A quartz watch tells the time, a mechanical watch tells a story.

This sentiment captures the core appeal. Choosing between quartz and mechanical is often a choice between pure utility and romantic artistry. Both are valid, but they represent entirely different philosophies of timekeeping.

The power source manual wind versus automatic

Within the realm of mechanical watches, a further division exists based on how the mainspring is wound to store energy. The two methods are manual winding and automatic winding. The manual-wind, or hand-wound, movement is the oldest type, tracing its lineage back to the first portable clocks. To power the watch, the owner must turn the crown, typically once a day, which tightens the mainspring. This daily ritual creates an intimate bond with the timepiece; it is a moment of connection and maintenance that many collectors cherish. Manual-wind movements can also be thinner than their automatic counterparts because they do not require the extra components for self-winding. This allows for the creation of very elegant and slim dress watches. Brands like Nomos Glashütte and many high-end Patek Philippe Calatrava models are famous for their beautifully executed manual-wind movements, often displayed proudly through a sapphire caseback. The act of winding becomes part of the ownership experience, a quiet moment of appreciation for the machine you are about to wear.

The automatic, or self-winding, movement was a revolutionary invention that added a layer of convenience to the mechanical watch. An automatic movement includes all the parts of a manual one but adds a key component; a semi-circular metal weight called a rotor. This rotor is mounted on bearings and pivots freely with the motion of the wearer’s arm. As it swings back and forth, it winds the mainspring, keeping the watch powered as long as it is worn regularly. If you take the watch off and leave it stationary, it will eventually run out of power after its ‘power reserve’ is depleted, which typically ranges from 40 to 80 hours or more in modern movements. The convenience of the automatic system has made it the dominant type of mechanical movement in the modern era. From the workhorse Seiko NH35 to the sophisticated calibers from Rolex and Omega, the automatic movement combines the soul of a mechanical watch with everyday practicality, making it the top choice for most consumers today.

The rise of the workhorse third-party movements

Not every watch brand creates its own movements from scratch. In fact, a vast majority of watches on the market, including those from well-respected Swiss brands and burgeoning microbrands, are powered by movements made by specialized third-party manufacturers. These are the unsung heroes of the watch industry, producing reliable, accurate, and cost-effective ‘ébauches’ or complete movements that other brands can purchase and install in their own cases. The most famous of these suppliers is ETA SA, a Swiss manufacturer owned by the Swatch Group. For decades, ETA movements like the 2824-2 and the Valjoux 7750 chronograph have been the industry standard, known for their robustness and serviceability. Any competent watchmaker in the world knows how to service an ETA movement, making long-term ownership straightforward and affordable. As ETA began restricting sales to brands outside the Swatch Group, another Swiss company, Sellita, rose to prominence. Sellita’s SW200-1, for example, is a near-identical clone of the ETA 2824-2, offering a readily available and equally dependable alternative.

Beyond Switzerland, Japanese manufacturers also play a critical role. Miyota, part of the Citizen Group, is a giant in the industry. Its 9000 series movements are praised for their thinness and reliability, offering a high-beat sweep that rivals many Swiss offerings at a fraction of the cost. Similarly, Seiko Instruments Inc. (SII) provides its unbranded NH series movements, like the ubiquitous NH35, to countless microbrands around the globe. These movements are celebrated for their incredible durability and value, allowing new and smaller brands to create compelling and accessible automatic watches. Using a third-party movement is not a sign of a lesser watch; rather, it is a smart business decision. It allows brands to focus their resources on unique case designs, high-quality dials, and overall finishing, while relying on a proven, dependable engine inside. This ecosystem has fueled a massive wave of creativity and accessibility in the watch world, particularly in the sub-$2000 price bracket, giving consumers more choices than ever before.

Product Recommendation:

- Timex Women’s Expedition Metal Field Mini 26mm Watch

- Casio Sport Watch LW-204-4ACF

- BUREI Men Watches Fashion Stainless Steel Analog Quartz Watches Business Waterproof Wristwatch,Fathers Day Gift for Men

- Accutime U.S. Polo Assn. Classic Men’s Quartz Metal and Alloy Watch, Color:Black (Model: USC80383)

- Timex Expedition Scout 40mm Men’s Analog Watch | INDIGLO Backlight and Luminous Hands | Durable Comfortable Adjustable Strap | 24 Hour Time | Rugged Outdoor Watch | 50M Water Resistance

The prestige of the in-house movement

In direct contrast to watches using third-party calibers are those that boast an ‘in-house’ or ‘manufacture’ movement. This term signifies that the watch brand has designed, developed, and manufactured its own movement entirely within its own facilities. This is a monumental undertaking that requires immense investment in research, development, machinery, and skilled watchmakers. For this reason, in-house movements are typically found in watches from luxury brands and are a significant mark of horological prestige and capability. A brand that achieves vertical integration, controlling every aspect of its watch’s production from the movement to the case, is considered a true ‘manufacture’. Rolex is perhaps the most famous example; every single movement in every Rolex watch is designed and built by Rolex. This allows them complete control over quality, performance, and innovation. They can tailor a movement’s specifications, such as increasing power reserve or improving magnetic resistance with materials like their Parachrom hairspring, to perfectly suit a specific watch model.

Omega, with its Co-Axial Master Chronometer calibers, is another leader in in-house technology, pushing the boundaries of anti-magnetism and chronometric performance. Patek Philippe, A. Lange & Söhne, and Jaeger-LeCoultre are other titans of watchmaking whose reputations are built upon the foundation of their extraordinary in-house movements. The benefits go beyond technical specifications. An in-house movement allows a brand to create a unique movement architecture and apply specific, proprietary finishing techniques, turning the movement itself into a work of art. For collectors, an in-house movement represents the purest expression of a brand’s identity and watchmaking philosophy. While often more expensive to service, the exclusivity, innovation, and craftsmanship associated with a manufacture caliber are, for many, the very definition of luxury horology. It is a statement of a brand’s commitment not just to telling time, but to advancing the art of watchmaking itself.

Beyond timekeeping exploring complications

Once you understand the basic engine of a watch, the next layer of complexity and fascination comes from ‘complications’. In horology, a complication is any function on a watch that does something other than display the hours, minutes, and seconds. Even the most common features, which we often take for granted, are considered complications. A simple date window, for instance, is a complication. A day-date function, showing both the day of the week and the date, is another. One of the most popular and recognizable complications is the chronograph, which is essentially a stopwatch function integrated into the watch movement. Activated by pushers on the side of the case, a chronograph uses a series of additional hands and sub-dials to measure elapsed time, a feature that is both technically complex and highly useful. The Omega Speedmaster, famous as the ‘Moonwatch’, is arguably the most iconic chronograph in history.

From there, complications can become exponentially more intricate and expensive. A GMT or dual-time complication allows the watch to display two time zones simultaneously, an invaluable tool for pilots and frequent travelers. The Rolex GMT-Master II is the benchmark for this category. Moving into ‘grand complications’, we find mechanisms of breathtaking complexity. The perpetual calendar is a mechanical marvel programmed to correctly display the date, day, month, and even leap years, automatically adjusting for months with different numbers of days without needing manual correction for a century or more. A tourbillon, invented to counteract the effects of gravity on a pocket watch’s accuracy, places the escapement and balance wheel in a rotating cage, a visually stunning display of horological mastery. At the highest echelon are complications like the minute repeater, which chimes the time on demand using tiny hammers and gongs. Each complication adds layers of gears, levers, and springs to the base movement, requiring immense skill to design, assemble, and regulate.

Finishing and decoration the art within the machine

The final element in our movement matrix is one of pure artistry; the finishing and decoration applied to the movement’s components. While these details may not affect the timekeeping performance of a basic watch, they are a critical indicator of craftsmanship and a hallmark of high-end horology. In fine watchmaking, every part of the movement, even those hidden from view, is meticulously decorated by hand or with specialized machines. This practice originated to remove microscopic burrs from manufacturing and to trap dust, but it has since evolved into a significant art form. When you look through an exhibition caseback on a luxury watch, you are seeing a canvas of these techniques. One of the most common is ‘Côtes de Genève’, or Geneva stripes, which are beautiful wave-like patterns engraved onto the bridges and rotor of the movement. ‘Perlage’, or circular graining, consists of small, overlapping circles applied to the main plate and other flat surfaces.

‘Anglage’, or chamfering, is the process of creating a polished, 45-degree angle on the edges of bridges and levers. When done by hand to a high standard, these polished edges can shine like diamonds and are a true sign of artisanal skill. Even the screw heads are often polished to a mirror finish or thermally blued to a vibrant color. These decorative elements serve no practical purpose in a modern sense, but they represent a dedication to excellence that defines the difference between a simple time-telling device and a piece of mechanical art. Brands like A. Lange & Söhne and Patek Philippe are revered for their immaculate movement finishing, where every surface is treated with artistic care. This attention to detail demonstrates a respect for tradition and a pursuit of perfection that elevates a watch movement from a mere machine to an object of profound beauty, worthy of being passed down through generations.

By breaking down a watch’s engine into this ‘Movement Matrix’, the seemingly complex world of horology becomes far more accessible. At its core, any movement can be understood by asking a few simple questions. Is it powered by a battery or a spring? Is it wound by hand or by motion? Was it made by a specialist supplier or by the watch brand itself? Does it do more than tell time? And finally, has it been decorated as a piece of art? From the most affordable quartz watch to a six-figure grand complication, this framework provides a universal language for understanding the heart of the timepiece. This knowledge doesn’t just satisfy curiosity; it deepens your appreciation for the ingenuity, skill, and passion that goes into every single watch. The next time you look at your wrist, you won’t just see the time. You’ll see an engine with a story, and now, you have the tools to read it.